This article is part of a new series on Gaming Alexandria called Origin of Game, stories of how famous game companies came to be! These tales written by staff and guest authors draw on research gathered over the years and give a glimpse into the people who defined video game history. We hope these articles will stoke your desire to learn more about the developers and publishers who have made our world fun!

Doug Carlston sat in an office on the 82nd floor of the world’s tallest building and realized what a terrible mistake he had made with his life.

The trained legal professional in Carlston had been excited when he landed a job with Price, Cushman, Keck, Mahin & Cate in the Sears Tower in Chicago, Illinois. But he had never been one for stayed, safe work on water law around Lake Michigan.

Doug was ever adventurous. With his family he had traveled the world and before deciding on law as a profession he had spent time as a tutor in Botswana, later writing an English textbook on the Swahili language. Another move would do him good.

He packed his bags and moved to Newport, Maine; he’d lived in the state before training to be a lawyer. With a friend, Doug set up a law practice while on the side he built houses – living a tranquil, small town life and skiing at his leisure.

The trajectory of his life forever changed when he heard of a fellow lawyer who was innovating an unusual business practice. “I knew of a lawyer in Northern Maine who traveled around the area in a Winnebago camper that was fully equipped as an office and that included a microcomputer system;” Carlston wrote in his book Software People, a personal history of the early software market. “He was able to crank out wills, trusts, and deeds in a fraction of the time normally required for such work and at a fraction of the cost that most lawyers charged.”

This reawakened something in Doug. He had actually been a programmer in his college years. At a summer job in high school, he’d learned how to operate a giant, punch card-driven IBM mainframe. Using that experience, he procured computer work at the University of Iowa and later his alma mater Harvard University. “My fellow programming fanatics and I used to jam chewing gum into the locks on the doors of the chemistry building just so we could sneak in after midnight and play with the big IBM 1620.” he wrote. It had just been one interest among many, but something he’d not forgotten.

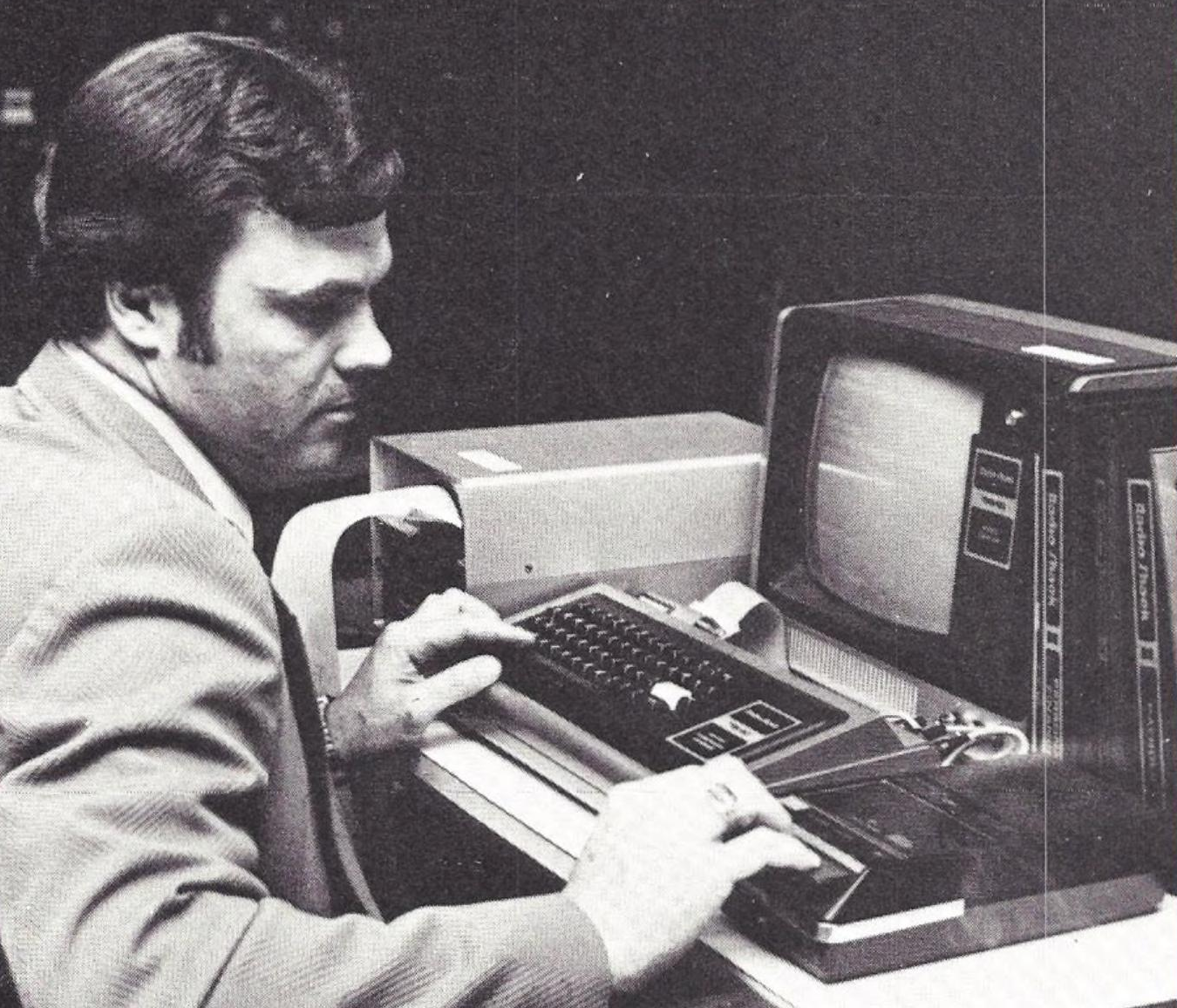

Doug’s interest was piqued. “Our law office needed to be able to compete,” wrote Doug. “We needed to computerize.” In 1978, he traveled to Waterville, Maine where a local Radio Shack was selling just the thing: Their own TRS-80 Model 1 computer, only $600 (before tax). He drove it home with hopes that he could use it to accelerate his business. Or at least, that’s what he told himself.

However, the TRS-80 was absolute rubbish for productivity. These early microcomputers had no great software for business; the first spreadsheet program wasn’t even yet on the market. With only 4-8kb of memory, they couldn’t even produce word documents of any real size – and good luck printing them out. Though some dedicated users found ways to make these limited computers work for them, it was far from simple.

But that didn’t really matter to Doug. His real reason for buying the machine had always been more recreational. “As I started to play with the computer, all my old fascination with the technology returned.” he explained in his book. His experiences with computers in college had only been vaguely interactive: the TRS-80 provided a truly personal computing experience.

He started learning BASIC, the lingua franca programming language of the microcomputer world. His first program was simple: A way to easily churn through tax and trust questionnaires at home. As he put that program together, he started to study what other programs were out there on the market. For the most part, instead of tax software, what he found were games.

A cottage industry of enthusiasts were creating all sorts of games for early microcomputers. User groups openly traded software – often based on programs from the type-in book 101 Basic Computer Games – as a means of connecting with others. Then there were early software publishers who would conglomerate batches of programs and sell them through mail order, advertising in newsletters and magazines.

This world was not totally new to Carlston. Games had never been a huge part of his life, but he had been aware of people playing computer games on his university mainframes. Early games for the TRS-80 were hardly impressive, with only text-based character modes and the limited data storage of cassette tapes. But as he started to fool around with the likes of Hamurabi and early text adventures, he started to feel there was something to the idea of creating a game.

Doug did eventually finish the software he created for his practice, but he never even used it on the job. Increasingly the subject of programming occupied his thoughts. “My legal briefs ended up with bits and pieces of programming code scribbled in the margins,” he wrote. “And I could hardly wait to get back to the office to key my ideas into the machine to see whether they worked.”

Unable to keep his mind from this distraction, Carlston threw himself into a new project that would become his first game. “Although I saw it as a weekend amusement,” wrote Doug. “That game was actually the beginning of the end of my law career.”

According to one profile on his career though, the program didn’t start as a game. Instead it, “began as a program to simulate life choices: Should I go to college, should I get married, etc.” Somehow out of this, his interest in science fiction took over. Doug had always been a voracious reader and had sampled the gamut of pulp sci-fi in his younger years, “Everything from Asimov to Zelazny.” he says.

:strip_icc()/pic1475145.png)

Though there were other science fiction wargames – including a few adapted to the TRS-80 like Starfleet Orion – he says there was no exact reference for the strategy game he was creating. Galactic Empire was an interesting beast, a planet conquering experience with touches of humor – like the often ridiculous letter-salad names. He fit the program into 300 lines of code, experiencing the thrill that comes from finishing a first game.

While it was personally edifying, Doug also thought Galactic Empire was good enough to sell. What would it be like if he could turn his weekend hobby into a profitable enterprise?

Computer game publishing of the 1970s was far from what one might call professional. The novelty of being able to buy software – rather than every user being expected to make their own – meant publishers sold just about everything they were sent. A publisher acted as de facto distributor of their games, which generally covered only a limited territory of mail order or limited selling into computer stores. This meant little quality control and no exclusivity requirement by the software provider.

To find publishers, Carlston looked inside the pages of the TRS-80 magazine 80-U.S Journal and sent the game to four software companies who’d placed an ad in its pages. Sneakily, he’d added a request to feed his newfound software addiction. “And, by the way, would they consider sending me their line of software, gratis, as part of the deal?” he wrote. Remarkably: Three of the companies took him up on that offer!

All three would publish Galactic Empire, including Cybernautics and The Software Exchange. The most important and professional of these outfits was Florida’s Adventure International. Scott and Alexa Adams were pioneering a new model of software publishing which had a national reach, selling into the growing number of computer stores across the country.

Alexa called Doug less than a week after he sent the program to work out the details. “Not only do we want to publish it,” he recalled her saying. “But we’ll be shipping tonight. I’ve already sold fifty copies.” No written contract needed – the Adams’ sent Carlston a $300 cheque a few weeks later.

The moonlighting lawyer greatly admired Adventure International, due in part to his own frustrations in acquiring software. One of the few programs he’d sought out was the game Microchess, published by one of the first professional software publishers for microcomputers, Visicorp. Despite Radio Shack having made a special deal to carry the program in their nationwide chain, Doug had to drive all the way from Maine to Boston to acquire a copy.

The quality of product from most publishers often matched that unsophistication in availability. Galactic Empire itself shipped with some significant bugs and had to be revised several times. That helped make Doug a better coder while also distracting him further from his legal duties.

With a healthy royalty coming in from game sales and a flagging interest in law, Carlston seriously considered becoming a full-time game programmer. He wasn’t certain whether it was a wise career move – all he knew was that he would be happier if he made a drastic change: like he had when moving out of the Sears Tower office two years previous.

In October 1979, Doug wrapped up his small time law practice and joined the ranks of the earliest professional game makers. “I had no idea whether the freelance programming business was going to continue to be financially viable, but I abandoned my law career anyway because the microcomputer software world drew me in a way that I found irresistible.” he wrote in retrospect.

But he was never a purely isolated individual. He was very connected to his family, two younger brothers and two sisters. The Carlston siblings had a very adventurous childhood owing to the rambling life of their father, a Presbyterian minister. The family had traveled the world and gained an interest in cultures far afield from their American roots which forever colored their optimistic outlook on the world.

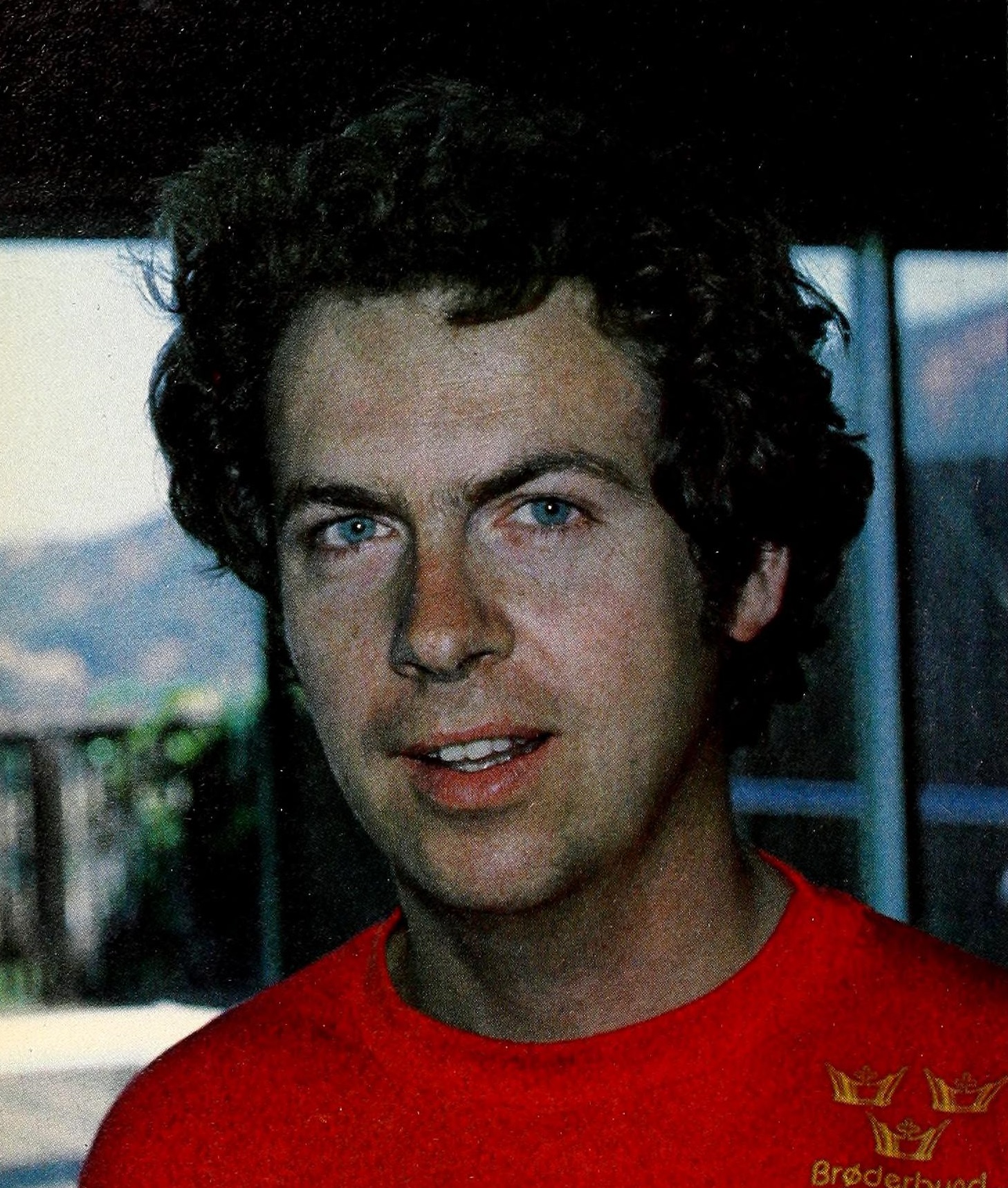

Gary Carlston – four years younger than Doug – was much like his brother in his easy pursuit of things that interested him. He had followed his family genealogy into Scandinavian studies and spent time coaching a Swedish women’s basketball team. He eventually found his way to Eugene, Oregon working for the non-profit March of Dimes before moving into a moribund business importing animal-shaped, silver bicycle reflectors.

The brothers had prior business arrangements. When first living in Maine, Doug had hired Gary and their sister Cathy to help him build houses. Later, Doug and Gary had attempted to create a tour guide business that was scuttled by governmental regulation – leaving Gary in debt to his brother.

Nevertheless, familial bonds and time eased any hurt feelings. When discussing their lots in life over the phone, Doug suggested that Gary could, perhaps, sell the games he was writing. “After all,” he penned. “Everyone else seemed to be making money doing it.”

Cutting out the middle man is the eventual hope of any financially inclined artist. As United Artists in film, Apple Corps in music, or Image Comics in the graphic arts, there is always an overriding hope that creators can avoid the tyranny of the money man by controlling their own business interests. Such was the case with Doug, who hoped his brother would take the suggestion seriously.

Gary didn’t immediately agree. None of his previous entrepreneurial adventures had worked out and he didn’t know left from right as it came to computers. Doug, with $12,000 saved, could afford to be risky.

And so he would. With vigor in his spirit, he decided to cross the country from Newport, Maine to Oregon and see if the roving life of a game programmer was one for him. In early winter of 1980, he prepared for the cross-country trip in his 1968 Chevy Impala. He shed most of his possessions: All he really needed was his computer and his mastiff Judge along for the ride.

“I was free, for the first time in years.” wrote the quixotic Doug. His journey along the northern part of the United States afforded him opportunities to visit old friends – who undoubtedly must have questioned his decision. Along the way he worked on his second game, Galactic Trader, in what was becoming a saga in his fabricated universe.

Doug’s vehicle was not as resilient as he was. The western end of the country became an endurance race. A snowstorm hit as he crossed through Wyoming. The Impala suffered continual issues including the windshield wipers not working, necessitating him to roll both windows down and stick his head into the blizzard as they headed up-mountain. Judge loved it.

Then at the crest of the Rocky Mountains, his transmission died. In the age before cellphones this could have meant a long wait for help… But thankfully he only had the downhill portion left to go. So onwards he drove, hoping to conquer the 3,000 mile journey before the car totally died on him.

On the last stretch, mere miles outside of Eugene, Oregon, Carlston’s luck ran out. The car would journey no more. Thankfully it was close enough to a phone to call Gary to pick up him – and his dog – at the end of this life-changing road trip.

Doug rented an apartment in the city and soon Gary joined him, being – as Doug characterized – “as usual, completely out of money and starving to death.” In this environment, Doug broached the subject of selling software again. This time Gary had nothing to lose. He finally acquiesced and solidified Doug’s long-term stay in Oregon.

Just to hawk games wasn’t going to be good enough. The brothers sought to create a publisher in the vein of Adventure International or the ascendant Personal Software of Visicalc fame. A market need clearly existed for intermediaries to place games and software in retail computer stores, so why not fill that need?

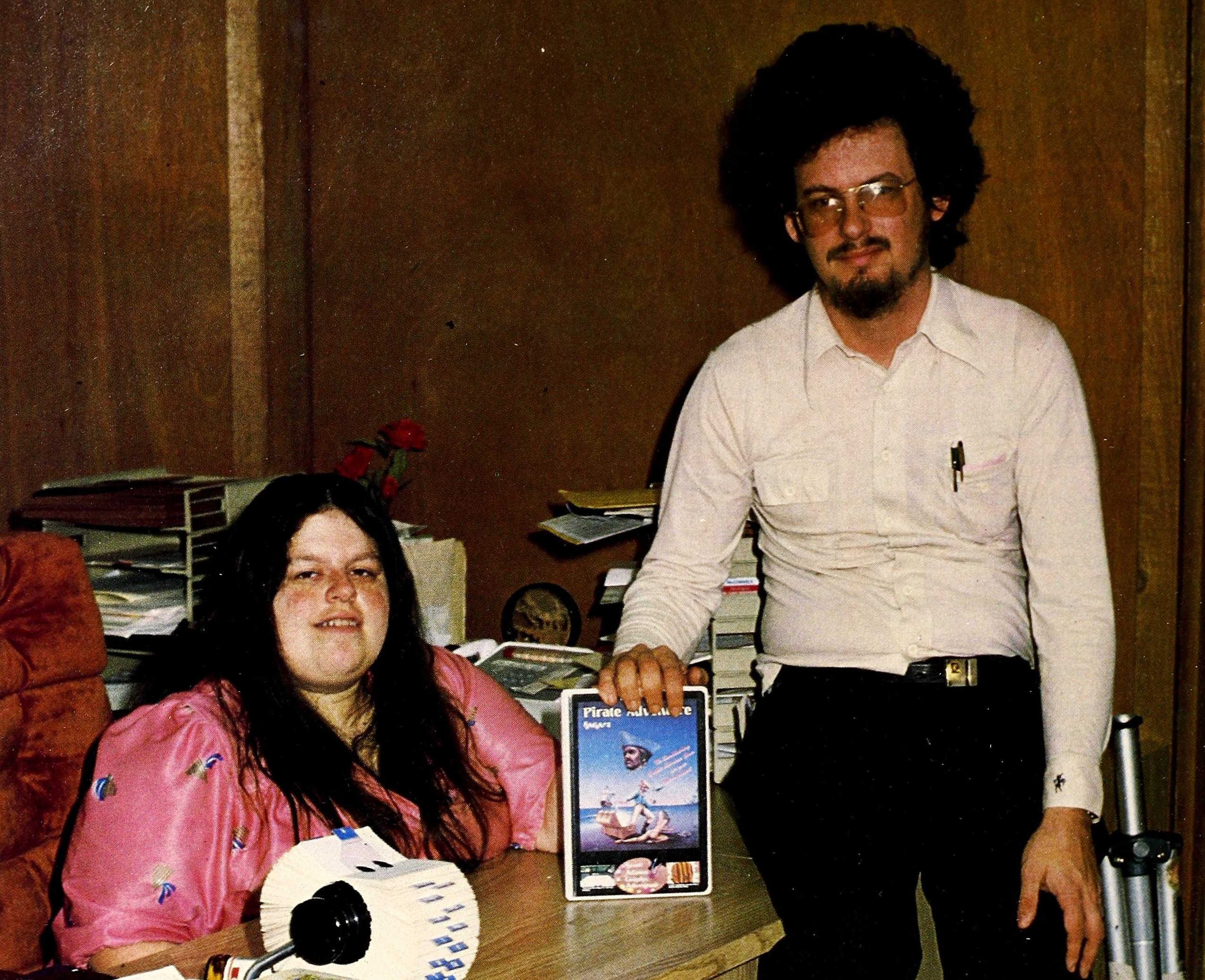

Gary and Doug also initially asked their younger brother Don to join the venture. Donal Carlston by coincidence had gotten into programming after exposure to the PLATO computer network in college. He was working on a simple Apple II game called Tank Commander, which seemed perfect for their venture. Ultimately, Don would not commit to the partnership, but this sibling collective greatly inspired the company’s identity.

In searching for a name for the partnership, Gary and Doug focused on the idea of “brotherhood” as a word to emulate. They approached it from their respective linguistic backgrounds: Gary from the related languages of Scandinavia and Doug from his experiences in Botswana, as well as their shared childhood growing up in Germany.

The exact road to the final name has been the subject of several stories told by the brothers over the years. This largely had to do with the existence of a contemporary political organization in South Africa with a suspiciously similar name to what they finally chose: The Broederbond. This secret organization of white locals of Afrikaans ethnicity were a notorious part of the politics of South Africa, being in large part responsible for the oppressive Apartheid policies in the latter half of the 20th century.

Doug Carlston has never denied knowing about the organization. Botswana, where he tutored, directly bordered South Africa, and he was even banned from the larger country for daring to teach an integrated school. Needless to say, his ethical worldview did not align with the organization and he emphasized that the final name “was not any form of homage to the Broederbond”.

But at the same time, the brothers have on occasion tried to say the other name had no influence whatsoever on their final decision. Elsewhere they claimed to have come to the name through the Swedish word for brother – broder – then adding the German “bund” to get the basic form. Then in tribute to how the number zero looked on low resolution computer displays and tomake it look more Scandinavian with a diacritic, they stylized the name as Brøderbund.

That alternative origin is appealing, but is contradicted elsewhere. At the time they were spinning up the operation, Doug was working on his third game, Galactic Revolution, which featured a secret society called the Broederbund. “I wanted a character, one of the opponents […] who worked for a guild of merchants and traders.” said Doug. “I called it ‘the brotherhood’ and I decided to make it a little more obscure.” According to Gary, it was the presence of that name in the game which inspired the company’s – initially in jest. “I originally suggested it as a company name as a joke because we didn’t think we’d sell enough software that anybody would ever see the name anyway.” Gary said.

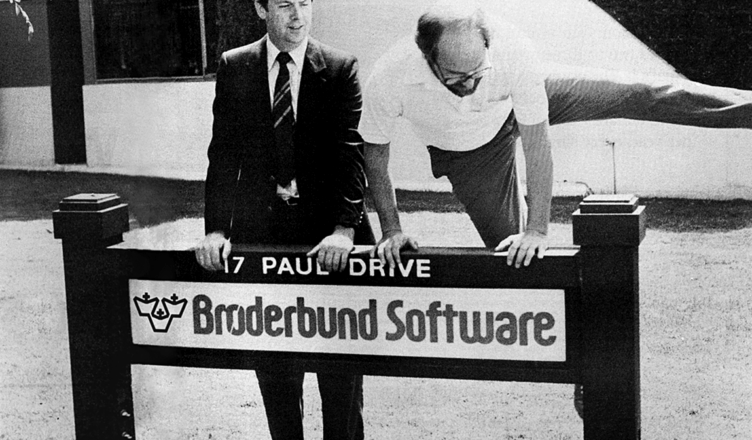

Brøderbund Software was setup as the backing for their publishing ambitions. Gary made the first sales call for their operation on February 20, 1980 while Doug was out of the apartment. Back across the country in Washington D.C., computer outlet The Program Store took a $300 order for their games. With that, Brøderbund started their journey to become one of the most important software publishers of the 20th century.

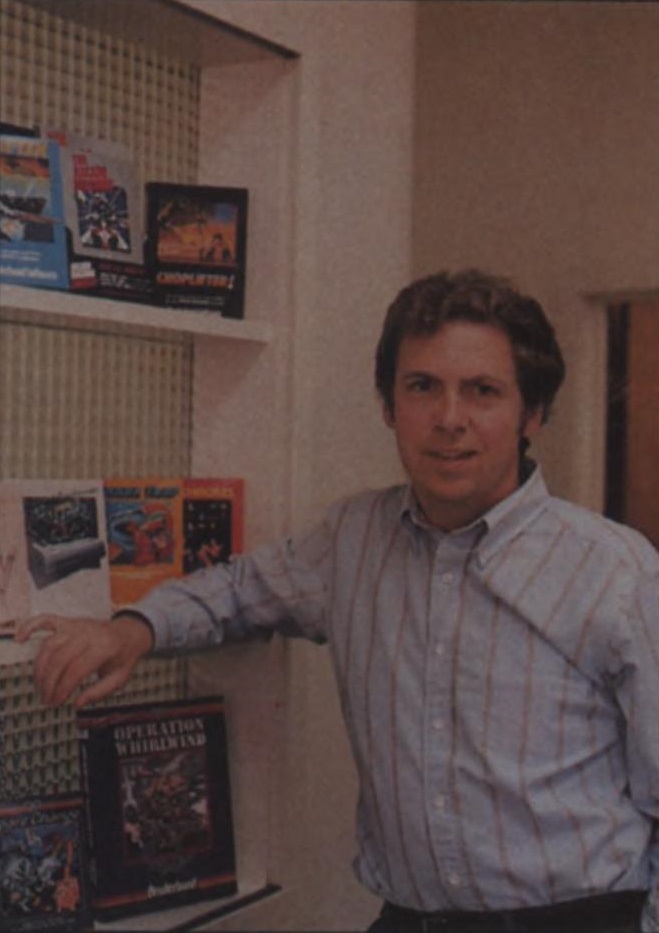

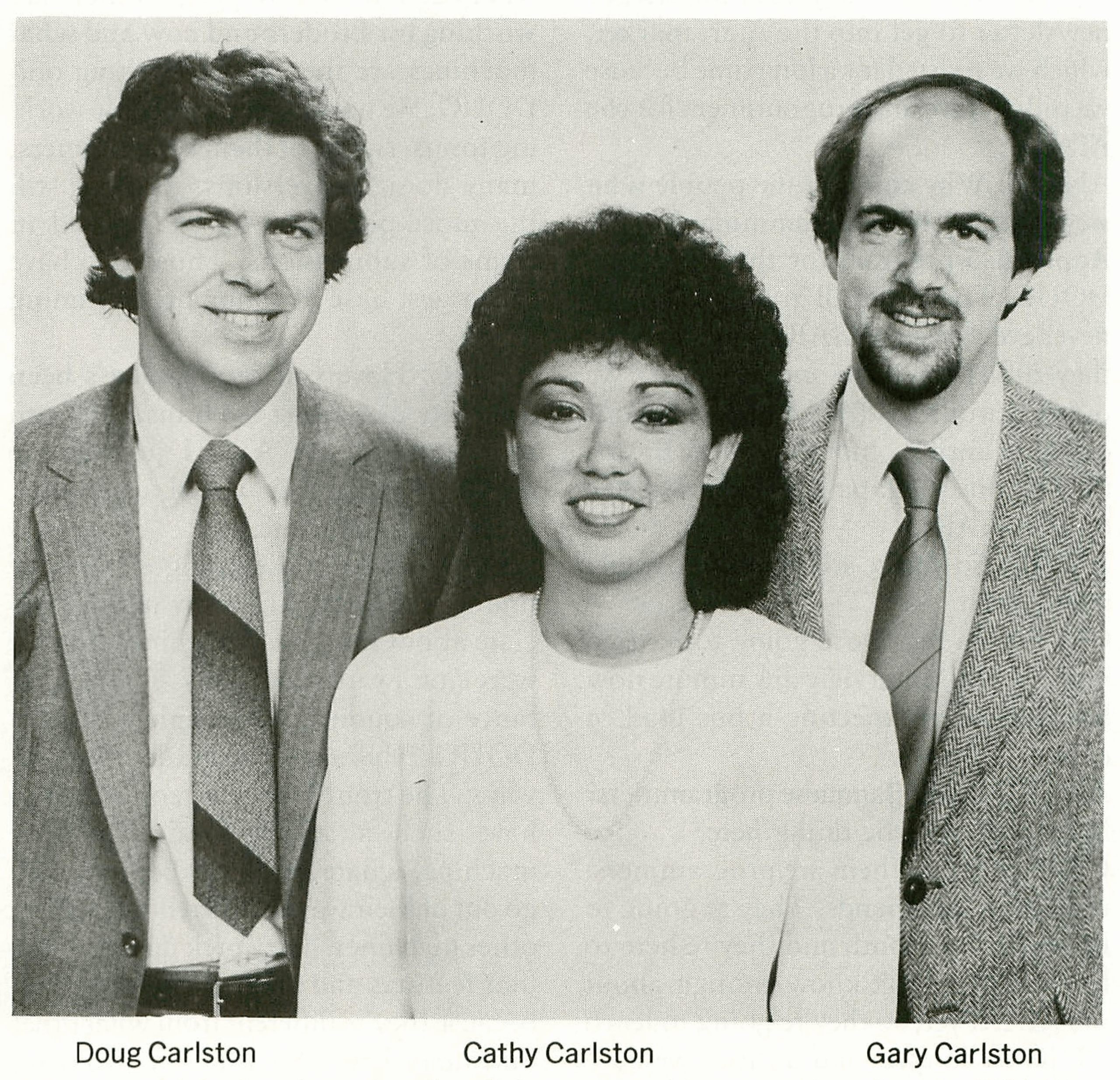

The vision for Brøderbund expanded ever outward from there, but would be built around the core of the Carlston family. Both siblings Cathy and Don would eventually join the company, with each sibling overseeing a specific part of the business. Doug quickly stopped programming and took over the non-game software, like Bank Street Writer and The Print Shop. Gary oversaw games publishing, fostering independently-developed classics like Choplifter and SimCity. Cathy Carlston started at the company in 1981 and later fostered their educational department including the later Carmen Sandiego franchise. Don Carlston – who became a noted psychologist – sold his board game Personal Preference through the New Ventures division of Brøderbund.

The company’s spirit and success made it a beacon for hopeful video game makers throughout the 1980s. Brøderbund helped to define the computer game industry, plus embody the mix of intellectual frivolity that Doug Carlston first experienced on his TRS-80 in Newport, Maine.

As for the pronunciation? That’s another story…

Huge thanks to Doug Carlston for his time answering questions and Kate Willaert for providing additional sources as well as editing the header image.

If you would like to submit an article for the Origin of Game series, contact Ethan on the Gaming Alexandria Discord. Thanks for reading!

Sources

Carlston, Douglas G. Oral History of Douglas Carlston. Interview by Tim Bergin, November 19, 2004. X3007.2005. CHM Oral History Collection.

Carlston, Douglas G. Software People: An Insider’s Look at the Personal Computer Software Industry. New York: Computer Book Division, Simon & Schuster, 1985.

Carlston, Douglas G. Email. June 28-30, 2025.

Carlston, Gary. Interview by David L. Craddock. Undated.

Robert Levering, Katz, Michael, and Milton Moskowitz. “Doug Carlston.” In The Computer Entrepreneurs: Who’s Making It Big and How in America’s Upstart Industry, 144–153, 1984.

Tommervik, Allan. “Exec Brøderbund: Saga and Star Craft Spell Success.” Softalk, November 1981, p. 52–59.

Uston, Ken. “A Family Affair.” Creative Computing, September 1984.